This morning our ship entered the first of the three gorges, named Qutang. At just eight kilometers it is the shortest of the three, but arguably the most spectacular, and is characterized by high, sharp peaks.

The Three Gorges mountains

Here we took our second excursion, transferring to a smaller boat that took us down a branching gorge to a port used by the traditional wooden boat rowers of the three gorges. These pea pod-shaped boats seat about 15 people in rows of three, and require a crew of four rowers (three in front and one in back) and one captain to steer the rudder at the rear. Rowing the huge wooden oars was clearly backbreaking work, but nonetheless some of the boatmen are as old as 60. Their people speak a particular dialect of Mandarin, and are considered to be one of China’s minority ethnic groups. Whenever two boats going in the same direction would approach one another, the men would pick up their pace and race until one had clearly overtaken the other. The local guide on each canoe taught the audience chants to use to encourage their crew, but ours seemed to particularly like a good old-fashioned American slow clap. I can’t imagine incentives for these races other than pride and a brief distraction from aching muscles. For one section, the rowers left the boat and pulled it by a rope from pathways on the shore, some of which have been etched into the mountain rock by thousands of years of use. This task is usually performed without clothing (I’m told that cloth has a tendency to chafe), but for the tourist’s benefit our haulers were wearing well-used jeans and polos.

Drastic differences in the The Gorges peoples’ way of life have come with the influx of tourism and modern influences, as well as the rising of the waters due to the Three Gorges Dam. They were forced to relocate their homes and much of the landscape on which they once sailed is now buried meters under the Yangtze. However, there are some positives to the lifestyle changes. What we saw of their new homes are clearly upgrades, a service that the government seems to have done an excellent job of providing across the board. In addition, deeper waters have made more of the waterways accessible by motorboat instead of only canoe. A run made twice a day by such a motorboat transports the area’s children back and forth to schools in only a half hour or so. Previously, the three or four hours needed to row to the schools was too great an obstacle to receiving a complete education.

A waterfall we passed during the canoe ride

Racing another boat

After returning to the cruise liner we passed Wushan, another county of Chongqing that was relocated because of the Three Gorges Project. We also passed Goddess Peak, which is a small, human-sized extrusion on the top of one of the mountains. Local lore claims that the spirit of a woman is in the peak, and generously grants the people favors when they are in need.

Just after passing Wushan we entered the second gorge, named Wu, which is 45 km long. The mountains here are shorter and rounder than those of Qutang, but the path of the River is much less linear. Before the sharpest curves of the snaking Yangtze, the ship had to blast its horn to warn any boats coming from the opposite direction. Every blast seemed to echo forever as it bounced back and forth along ancient mountains.

There are usually at least one or two other ships in view, although these range in size from the small canoes and motorboats of locals to coal and shipping container transporters headed upriver (we are headed downriver). Hydrofoils occasionally zip by–their speed is unmatched by all other vessels here.

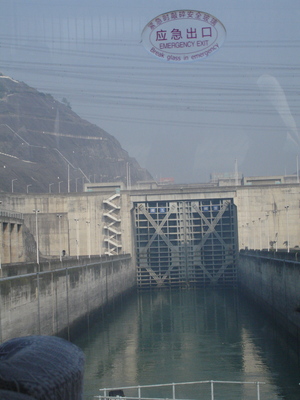

After several more hours of sailing through the final and extremely long (65 km) gorge, named Xiling, and an hour or so spent docked at a security checkpoint, we were finally cleared to pass through the five-step locks of the Three Gorges Dam. It’s hard to describe in words how imposing this structure is, especially in the black of midnight. A long array of lights to our right marked the main section of the damn, which in winter generates hydroelectric power from the water’s flow. Dead ahead were the two parallel roads of the locks, one for ships going upriver and the other for those going downriver. Our ship and four others pulled through the first lock into the second (the lower waterline in summer renders only four of the five locks necessary), so close to the cement walls that we could lean over the ship’s rails and touch them. After all the ships were in place, the gates behind us slowly closed and locked into position. Then the water began pumping out, and the walls appeared to rise higher and higher. Our boat rocked back and forth with constant period, every time returning to a relative position several feet lower on the wall. Eerie metallic screeches accompanied the drainage of the water, reminding me of the percussion in Eric Whitacre’s “Ghost Train.” At last the rocking stopped, and the gate in front of us slowly hinged inward. Our boat powered up and slowly advanced forward into the next lock.

By this stage it was about 2 AM, and we still had three or four hours to go before we would be free of the Dam and able to sail the last short leg of the journey to the dock in Yichang. Most of our group chose to go to bed, continuing to watch the concrete walls rise from our bedroom windows as we attempted to catch a few hours of sleep.

Looking out the back of the boat as Xinli chats with one of the staff members

The door to the next chamber

The door opens to allow us to move onward

Location: Yichang, China