Location: Dakar, Senegal and the Ile de Gorée

Bug Bite count: only 4 little ones on my foot!!! So much for getting eaten alive!

Showers are great. You know what ruins them slightly? When halfway through one you suddenly realise that you are in a third world country and you’ve already used more clean water than some people can get a hold of in an entire day or more. This is how, at 4:00 AM in the morning on Sunday, it hit me that I was in Senegal.

Because we are on a Francophone Studies programme, IES arranges a week-long trip to Senegal where we will hear lectures from Senegalese professors as well we see the sites in Dakar, as a chance to experience another francophone country. So on Saturday night we drove an hour south to Casablanca, where we then took a small plane to Leopold Sedar Senghor Airport in Dakar, Senegal. The plane was quite tiny and once again we loaded straight from the tarmac (envisioning scenes from the film Casablanca the entire time). I don’t know why I ever even bother trying to sleep on flights; you just get grumpy from trying to find a position where your neck doesn’t cry tears of aching pain. I did get a good chuckle though when I came to the sad conclusion during the in-flight meal that even airline chicken is better than college dining hall chicken. The flight took about 3 hours and because it was around 2:30 AM when we landed and dark outside, (although the mosquito attacks started before we were even out of the airport) I did not get to get a good impression of Senegal other than “hm there are a lot more lights than I expected.”

To describe Senegal is difficult. First, some geography. Dakar, the capital, is located on the westernmost tip of Senegal, surrounded on three sides by water. So even though it is hot and sticky, there is almost always a breeze if you are out in the open. Inside or in still areas, it is just as miserable as I imagined; you feel the moisture accumulate on all areas of your body and the air just hangs around you. What made it worse was that either a) I caught something on the airplane or b) I’m allergic to tropical countries, so I’ve spent every hour here sneezing and sniffling. So imagine being overheated in a humid, sticky moisture-laden place, then also feeling stuffed up and sneezy. But I digress.

Senegal is strange in that yes, it is a poor country, but there are some things that stick out as very strange. For example, nearly everyone has a smartphone, and Orange Money, the cell phone provider here, is the most heavily advertised thing. Another is that while the type/age of cars can vary, I’ll see five or six different people washing cars while we drive through Dakar each day. I guess keeping your car clean is just something you do here. Also, taxis have a tail of hair coming out of the back of their cabs, which is apparently a channel for their bad spirits (and I can see why taxi drivers would have lots of bad spirits- driving in Dakar is mental) to flow through the car and outside away from them. Interesting.

Another very very surprisingly common thing is the number of people exercising. Abiet, they live surrounded by water so running along the beach makes it tempting to work out anyway, but it’s not just one or two people running along. No, everyone is out jogging, stretching, or doing exercises. Apparently staying in shape is top priority for Senegalese men. It makes sense, everyone is tall, thin, and toned here. The women all wear gorgeous. vibrant, patterned two-piece dresses that flare at the waist and the ankles, complete with headpieces of the same cloth.

Masks found in the market

Sign on the Place de la Independence

But while they may be beautifully dressed and thin, they are not always pleasant to deal with as a Westerner when shopping, mostly because their version of shopping and haggling for prices is so different from ours. There are “boutiques” set up everywhere, even entire “arts villages” with winding streets of stalls and stands where they sell masks, jewelry, shirts, pants, paintings, ebony carvings, and the like (mostly designed for tourists but oh well). First they will do anything to get your attention. I’ve gotten Pretty lady, mademoiselle, sister, nice lady, and if you do tell your name to anyone, soon all the shopkeepers know it and call you personally. They’ll come up to you and block your way or take your arm and plead you to come look for a minute in their shop. If you so much as glance at something, they jump at the opportunity and take it off it’s place in the shop and present it to you up close, saying “For you, nice price, Senegalese price.” This all at first was annoying to me because I am more comfortable browsing slowly and looking at everything at my own pace, but I soon realised that this was just a part of their culture and I should not get angry. I was also very hesitant to haggle and bargain to lower the prices they gave- again not something I was used to. I’ve done it a few times in Morocco already, but here in Senegal they exaggerate the prices 50% or more what things are worth, so you absolutely need to be aggressive and get the price down. I found that you need to start with a really low price, then increase it slightly, ignoring all their high offers. Don’t act completely in love with the object; if they know you desire it badly, they won’t go as low as you want. Acting indifferent, setting the object down, and trying to walk away also works well. To be honest, I felt like a jerk arguing with these people in such a manner, but I just had to remember that the prices they wanted were tourist prices and not fair in the slightest. A Moroccan lady who was now studying in Senegal and friends with our IES guides, Mariam, spoke the local dialect and new what things were worth so she would help us get fair prices and barter with shopkeepers trying to swindle us. She helped me get this gorgeous painting of Africa that I’m very excited to hang in my dorm.

Even Senegalese university students all do their laundry on the same day.

Monument of the African Renaissance. Rather controversial, it has been decried as “vaguely communist” as well as “immoral” for the shortness of the woman’s skirt.

But other than buying very cheap Senegalese souvenirs, we actually have a very informative yet fun week. Each morning we would have breakfast at the hotel, then drive somewhere, whether it be the Museum of African Art, the local University, the Belgian Embassy, or just around Dakar for a tour, learn about the place, then have a lecture there. We talked about Senegalese migrants, National issues, the history of Senegal, the slave trade, and diversity in Senegal. After lunch we would normally have another lecture, then the late afternoon off to do what we wanted. We walked around downtown, saw the Presidential Palace, and swam in the hotel pool. On Wednesday we even went out to the Zoo…which was really depressing. The animals had hardly any room in their enclosures and there was trash everywhere. But we saw lions and a tiger and antelope and emu and baboons that got very angry and threw stuff (poo) at us!

Another venture out was to Ile de Gorée, Goree Island, which is 2 kilometers off the southern shore of Dakar and was used as a minor slave shipping post for the Atlantic Triangle Trade. Although only about 100 slaves came out of Goree headed for the Americas each year (other Senegalese ports had many more), today is serves as a monument, museum, and tourist attraction for the slave trade in general. Le Maison des Eslaves (the House of Slaves) is a landmark commemorating those who were enslaved by the Europeans and shipped off from Africa. The haunting feel of the place was slightly dimmed by the hundred or more schoolchildren on a field trip on the island who were more interested in playing on the beach than the historical significance of the island itself. Indeed, Goree was beautiful, essentially a tropical island, with even more vendors trying to sell you souvenirs.

Ile de Gorée.

This famous statue comes from Guadeloupe and commemorates when the French abolished slavery.

Another really fun experience was eating a traditional Senegalese meal with a host family of an IES student here. They eat in a circle on the floor around a huge communal dish, using only their right hand, as the left is considered dirty and in rural villages is used for bathroom purposes, hence the need to keep is separate from your food. So far we’ve had lots of fish, chicken, shredded carrots, shrimp, and french fries (they come with every meal I’m not kidding it’s strange). If it’s not a huge communal dish, then the fish or chicken comes on sticks and it’s called brochette (essentially their version of a kebab). However, the best thing I found in Senegal was the juice. In addition to mango jus, which is delicious in it of itself, they also have a drink called cocktail, which is mix of juice from the Baobab tree fruit called buyue and juice from hibiscus flower nectar, called bisap. It’s sweet and delicious and wonderful.

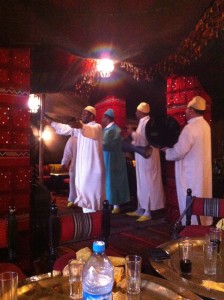

Finally, on Friday morning, we experienced what led to this week’s lesson. Sam, the former IES student, arranged a drumming and dancing workshop with a group of friends she has made here who live by a very Senegalese philosophy; a l’aise, that is, to take it easy, to be comfortable and peaceable. They drink tea and play drums and guitar under a tree every day and generally “live acoustically”. Learning to drum on a djembe and dance traditional Wolof Senegalese dance was very enriching and fun. They were such laid-back, fun, and calm people, and their teachings really conveyed just why the Senegalese believe in “a l’aise” so much. It’s just about not worrying about things as much and not comparing your life to others. That was particularly applicable to us as Westerners visiting Senegal. Yes, flushing toilets were hard to come by and the haggling was a shock and people were overly forward with us and our phones didn’t work here, but the key was just to not compare Senegal to our lives in the States or even in Morocco. Don’t compare, because they you won’t enjoy it as it is face-value. Don’t compare, because then you won’t be “a l’aise”

Location: Dakar, Senegal

After lunch it was time to catch our ferry to Spain- which was so much closer than I’d thought! The ferry ride was only an hour, and after 20 minutes I could see the Spanish coast before Morocco even disappeared from view. We landed in Tarifa, the closest port, and after another bus ride we were in our hostel for the night in Cadiz, Europe’s oldest city! It was also where Christopher Columbus set sail on his second voyage from, which makes sense because Cadiz is essentially just an outcrop surrounded on three sides by sea and connected to the mainland by a strip of land less than a mile wide. However our plan was to only stay the night, visit Seville the next day, and come back to Cadiz on Saturday so that when we had to travel the whole way back to Rabat on Sunday were closer and had less milage to cover in one day.

After lunch it was time to catch our ferry to Spain- which was so much closer than I’d thought! The ferry ride was only an hour, and after 20 minutes I could see the Spanish coast before Morocco even disappeared from view. We landed in Tarifa, the closest port, and after another bus ride we were in our hostel for the night in Cadiz, Europe’s oldest city! It was also where Christopher Columbus set sail on his second voyage from, which makes sense because Cadiz is essentially just an outcrop surrounded on three sides by sea and connected to the mainland by a strip of land less than a mile wide. However our plan was to only stay the night, visit Seville the next day, and come back to Cadiz on Saturday so that when we had to travel the whole way back to Rabat on Sunday were closer and had less milage to cover in one day.